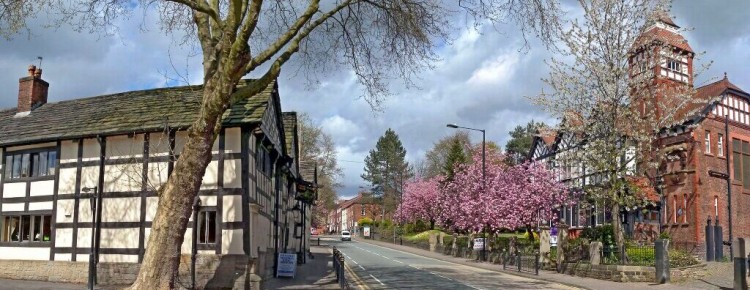

Ye Olde Boar’s Head P.H. (left) and Jubilee Library (right) on Middleton’s Long Street look lovely in spring with the cherry blossom.

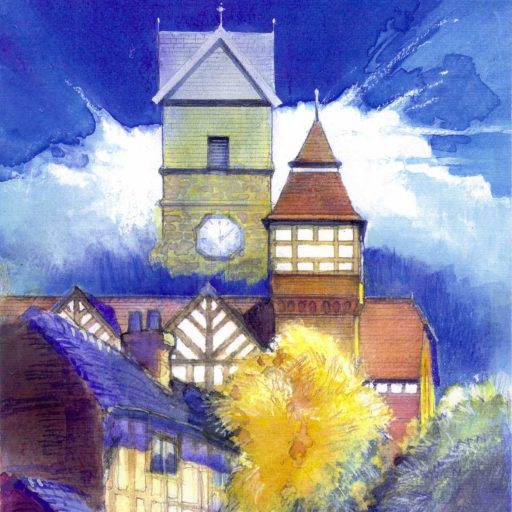

The library is an unusual early Arts & Crafts building that lies in the pleasant Jubilee Park at the centre of the Middleton conservation area. As well as the timber-framed pub, close by are St. Leonard’s Church and the Old Grammar School – the oldest pub, church and school in the Manchester region. Opposite is the unique Arts & Crafts Church – the heart of Middleton’s Golden Cluster of heritage.

The Jubilee Library is open every day except Sundays and Bank Holidays. Latest opening times are HERE. It includes the Middleton Local History archive – which contains a wealth of historical resources including books, photographs, maps and newspaper archives. It has free WiFi, a study area and photocopier and is as perfect for a relaxing browse as it is for serious study.

Jubilee Library is a very unusual building with several interesting Arts & Crafts features. For example, old fashioned pegged oak timber framing is combined with reinforced rolled iron columns and girders and a reinforced concrete floor. Inside, it looks like a cotton mill. The design looks both to the past and the future for inspiration.

The architect was Lawrence Booth, a Bury designer then in his 50s who was noted for his large hospital designs. He won the competition to design the building, responding to the competition requirement that the new building should be in keeping with the Ye Olde Boar’s Head P.H. opposite. However, the idea of using oak timber framing and a rustic oak porch all traditionally pegged some way beyond what an 1880s understanding of ‘in keeping’ might mean. The asymmetric design is also very unlike his other library at Newton Heath, Manchester (now demolished), which was typically Victorian. Is it really possible that this designer of hospitals and workhouses created Jubilee Library on his own?

The requirement the the Library should be in keeping with the Olde Boar’s Head almost certainly came from Edgar Wood’s influence, as such ideas were almost unheard off at that time. There is also a rawness and vigour to the design that is easier to attribute to Edgar Wood than to Lawrence Booth. The timber framing is functional without the usual Victorian elaboration, while the concrete floor and iron girders and posts impart a very robust mill-like aesthetic to the interior. Some details, like the art nouveau finial to the tower and having a rustic timber porch are also very Wood-like.

Prior to 1889, Edgar Wood had never used the masonry materials of the library, white headed common bricks with Ruabon brick dressings, red roof tiles and red Cheshire sandstone. However, that year as the Library was being erected, he built two minor commissions, the Albion Inn (demolished) and Middleton Cricket pavilion in precisely these materials. Perhaps, he was trying out Lawrence Booth’s palette for himself. He also built a drinking fountain at Birch (listed grade II) using the same red sandstone with an ornamental plaque very similar to the one on the Library, albeit much smaller.

Edgar Wood’s father, T. B. Wood and several of Edgar’s clients, including the Schwabe family, were leading members of the Library committee and were the principal benefactors of the public subscription. Surely, they would have wanted to commission Edgar, after all he had just built a school for the Schwabes at Rhodes (listed grade II). But how could he even enter such a competition, let alone win it?

Edgar was closely involved with other aspects of the Jubilee project. He had designed and painted an elaborate carved frame certificate for the retiring librarian and had erected a vernacular oak framed structure with a stone roof for a Jubilee drinking fountain, paid for by his step-mother.

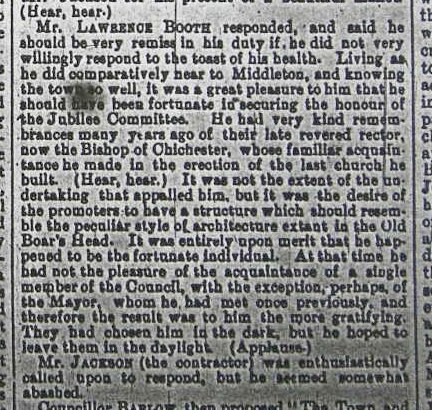

At the laying of the foundation stone, Lawrence Booth seemed rather too keen to point out how he had not met the members of the Council. He also mentioned it was not the extent of the undertaking that overwhelmed him but “the desire of the promoters to have a structure which would resemble the peculiar style of architecture extant in the Old Boar’s Head”.

The most likely explanation is that, while Lawrence Booth was the project architect, Edgar Wood was a silent joint designer. This form of ‘ghosting’ was common at that time. Such a route would have allowed the committee to acquire an Edgar Wood design while avoiding local controversy. Not only were there the family ties to hide but also Edgar Wood’s designs were not universally popular in the small town of Middleton! Edgar Wood had to be hidden from the public gaze at least two other times.

If this was indeed the case, Lawrence Booth may have had second thoughts when the project had been completed because, in 1890, he gave a lecture about “Commissions’ where he “depreciated all secret commissions, and advocated complete candour on the part of the architect towards his client, as ‘suspicion always dogged the steps of secrecy'”.