Lydia Ernestine Becker (24 February 1827 – 18 July 1890) was a scientist and early leader of the British suffrage movement. She is best remembered for founding and publishing the Women’s Suffrage Journal between 1870 and 1890.

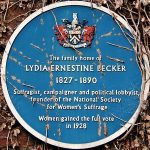

Lydia’s grandfather, Ernest Becker, had come to Manchester from Germany in the late 1790s and made his money from manufacturing acid which was used in the cotton industry. The family lived in Foxdenton Hall, off Foxdenton Lane, Middleton. At the hall, which lies in Chadderton, there is a blue plaque to Lydia’s memory.

Lydia Becker was educated at home where she studied botany and astronomy from the 1850s onwards, winning a gold medal for an 1862 scholarly paper on horticulture.

Five years later, she founded the Ladies’ Literary Society in Manchester. She began a correspondence with Charles Darwin and soon afterwards convinced him to send a paper to the society. In the course of their correspondence, she sent a number of plant samples to Darwin from the fields surrounding Manchester. She also forwarded Darwin a copy of her “little book”, Botany for Novices (1864). Lydia was one of a number of 19th-century women who contributed, often routinely, to Darwin’s scientific work.

She was recognised for her scientific contributions, being awarded a national prize in the 1860s for a collection of dried plants prepared using a method that she had devised so that they retained their original colours. She gave a botanical paper to the 1869 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. A career in science awaited her but, although Botany remained important to her, but her work for women’s suffrage took over her life.

In January 1867 convened the first meeting of the Manchester Women’s Suffrage Committee, the first organisation of its kind in England. Several months later, a widowed shop owner, Lilly Maxwell, mistakenly appeared on the register of voters in Manchester. She was not the first but she was a good opportunity for publicity. Lydia visited Maxwell and escorted her to the polling station. The returning officer found Maxwell’s name on the list and allowed her to vote.

On 14 April 1868, the first public meeting of the National Society for Women’s Suffrage in the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, Lydia moved the resolution that women should be granted voting rights on the same terms as men. She subsequently commenced a lecture tour of northern cities on behalf of the society and, in 1869, was successful in securing the vote for women in municipal elections. In 1870, Lydia and her friend Jessie Boucherett founded the Women’s Suffrage Journal, the most popular publication relating to women’s suffrage in 19th-century Britain. Lydia began organising speaking tours of women – a rarity in Britain at that time. One local Lydia Becker lecture in the Temperance Hall at Middleton was presided by Thomas Broadbent Wood, the father of Middleton architect Edgar Wood, who was a strong supported of Women’s suffrage.

At an 1874 speaking event in Manchester organised by Lydia, a fifteen-year-old Emmeline Pankhurst experienced her first public gathering in the name of women’s suffrage. Lydia became the chair of the Central Committee of the National Society for Women’s Suffrage.

Lydia Becker argued there was no natural difference between the intellect of men and women and was an advocate of a non-gendered education system. She also argued for the voting rights of unmarried women which made her the target of frequent ridicule in newspaper commentary and editorial cartoons.

In 1890, Lydia visited the spa town of Aix-les-Bains, where she fell ill and died of diphtheria, aged 63. Rather than continue publishing in her absence, the staff of the Women’s Suffrage Journal decided to cease production.